“Wolf, Are You There?” is a game of hide-and-seek for children whose scenography is drawn from by all theatrical events. In it some children scattered about the perimeter of the playground sing a song to the wolf, who is waiting in a corner.

“Let’s walk through the woods

When the wolf isn’t there.

If the wolf were there

He’d eat us up

But he’s not there

So he won’t.”

Then comes the crucial moment where the passers-by ask the wolf directly, “Are you there, wolf? Do you hear me? What are you doing?”

The wolf, who is supposedly dressing, inevitably replies, “I’m putting on my shirt” or “I’m putting on my socks” or “I’m putting on my pants.”

In fact the wolf can choose, and herein lies the suspense of the game, between leaping out after his first reply saying, “Here I am! Here I am!” or making the pleasure last longer by replying twice, three or even seven times before he eventually says, “Here I am! Here I am!” jumping out to chase after the passers-by, and the last person to escape the wolf wins the game.

But from “Wolf, are you there?”, the game of hide-and-seek for children, to the masked ball –the ceremony or entertainment reserved for adults– there is only a short step that is easy to take because it is still a matter of hiding or concealing oneself, of showing oneself and observing. Besides, the presence of the wolf is an added reason that emphasises the similarity between the game and the ceremony when we realise that, at least in French, the word “wolf” (loup) designates precisely the black leather mask that guests at a masked ball wear. Indeed this black mask, which imitates the face of a wolf when placed on the face, conceals even better the identity of the participant if it makes his eyes shine. We cannot fail to add that in the children’s game the wolf is supposed to wear people’s clothes while in the masked ball the guest borrows the animal face of a wolf.

Let us go back in time. In 1918 in Paris the writer André de Lorde, nicknamed “The Prince of Terror” and whose numerous works form part of the Grand Guignol theatre, published Cauchemars, a collection of short stories illustrated by Gus Bofa. The titles of the stories, such as “L’Horrible expérience”, “Le Bal rouge”, “Mystérieux attentats”, “L’Agonisante”, “Morphinomane”, “Au Pays des Supplices” or “L’Enfant mort”, reveal the horrifying, anguished genre of terror. Let us pause at “Le Bal rouge”, the story of an optical illusion and a tragic misunderstanding. The countess of Lerne, who holds a splendid masked ball, thinks she recognises her husband, who had left her years before, among the guests. However, the character in disguise is the chief of the Mask Gang. The countess is strangled to death.

On Monday, 13th January 1919, André Breton sent a folding collage-letter to his friend Jacques Vaché, still mobilised in Belgium. André Breton, who wrote his initials on one of the folds of the document, managed to squeeze into a plain envelope a device with forty-five centimetres of surprises[1]. In fact, he expected Jacques Vaché, who he did not know had died the previous Monday after taking a large amount of opium at a hotel in Nantes, to notice the background noise of the movements and events going on at the time among the hotchpotch of printed cut-outs, mutilated images, selected labels, folded pages and copied lines. This collage-letter, which anticipates Littérature, La Révolution surréaliste and Anthologie de l’humour noir, is eloquent about its addressee, about the inventor of umour without an h, especially in the drawing by Gus Bofa representing a burglar on a dark night, wrapped in a cloak and hiding behind a mask. One can guess Breton had cut out the drawing by Gus Bofa illustrating “Le Bal Rouge” and showing a Fantômas-style masked character, albeit even more disquieting.

We shall take a look at Gus Bofa’s drawing, cut out exactly from page 13 of Cauchemars. We can see that Breton has added two more cut-outs. On the one hand, the collage-maker, after cutting out a blank page with the printed name “crème 204” and the words “40 c le metre” written in pencil (which would seem to mean that the blank page had been used to wrap an article of haberdashery), decided to stick this cut-out piece of paper at the bottom of Gus Bofa’s illustration in such a way that it covered most of the inscription and only left the first word visible: “The mask [recovered its immobility]”. Then he wrote in his own hand in blue ink on the blank page these fatal words, “It was you, Jacques!” identifying forever more the man in the black mask from “Le Bal Rouge” with his friend Jacques Vaché. On the other hand, as if Gus Bofa’s drawing was not explicit enough, the collagist inserted vertically across the drawing a new cut-out saying, “DOuble faCE”, whose graphics and symmetrical treatment of the two terms emphasised the content of the message. In short, Breton managed to frame Gus Bofa’s already very expressive drawing with a horizontal inscription that said, “It was you, Jacques!” and a vertical one that said, “DOuble faCE”, thus identifying Jacques Vaché with a guest at a masked ball in a black mask but also with a character that proposes a new face every day behind his new disguise. On the other hand, we cannot exclude the possibility that when he wrote “It was you, Jacques!” in the past tense, Breton had a premonition about his friend’s death.

All André Breton’s career as a Surrealist –to use a rather pompous expression– developed under the sign of the collage, as he had indeed announced in July 1918 in his poem “Pour Lafcadio”, where, without counting the private joke shared with André Gide, there are several borrowings from Arthur Rimbaud and his friends Louis Aragon, Théodore Fraenkel and Jacques Vaché.

“It is better to let them say

that André Breton, Collector of Indirect Taxes,

devotes himself to the collage

while awaiting retirement.”

The collages made by Breton and his Surrealist colleagues or friends took place in three fields: 1. that of matter, a conjunction of images that give rise to a new object; 2. that of the group, a friction of individuals that gives rise to a passion; and 3. that of time, an objective randomness that signals the existence of a magnetised duration.

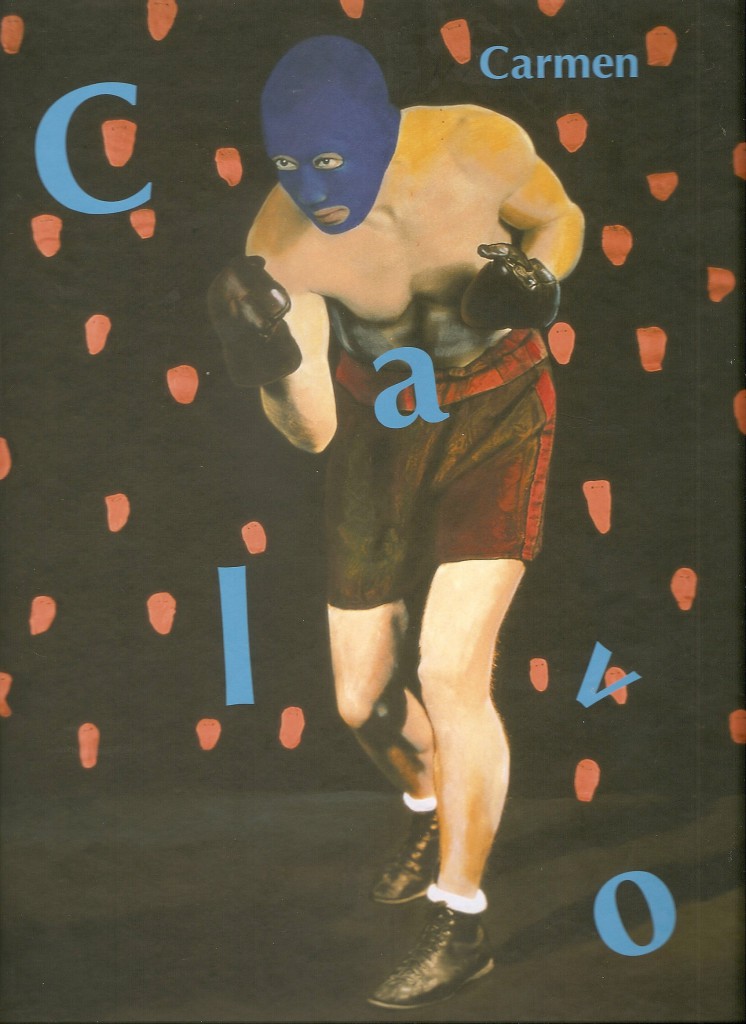

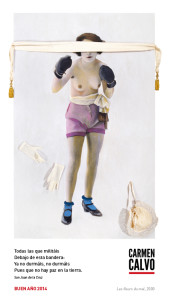

Carmen Calvo the collagist

Should we not say at the outset that Carmen Calvo is also a Surrealist collagist? Born a little over fifty years after André Breton, our current collector of Indirect Taxes had plenty of freedom to inventory and reinvent the Surrealist legacy. As we suggested at the beginning, she embarked upon a great game of hide-and-seek with the wolf. But her game of “Wolf, are you there?” has the particularity that everyone participates in it, girls and boys, adults and children. It has the other particularity that it seems to promote a new rule of the game: that all the players or nearly all of them should look like the wolf. Or, more exactly, that they should all wear a black leather or velvet mask on their faces. Or dress up and make up a hundred different ways with a theatrical or carnival mask, with a robber’s or terrorist’s balaclava helmet, with a tulle veil, with an antiseptic mask that covers the nose and mouth, with a blindfold a game of blind-man’s buff or execution or, finally, with a facial or beauty mask consisting of a layer of cream applied to the face whose secret Carmen Calvo knows, so violently and unevenly coloured this paste is, without forgetting, naturally, the placing of a label or rectangular shape over the eyes to preserve or delete the person’s identify.

Thus, the face wishes to be totally or partially masked, curtailed, mutilated and stripped of most of its attraction. What do these operations of concealment or diminishment mean, these surgical transplants, these disappearing procedures, these untimely interventions on the sacred human face? There is nothing to prevent us from thinking that Carmen Calvo, as an artist, repeats the attitude of the young philosopher Descartes when he wrote on the first page of his private diary, “Just as actors put a mask on their faces when they are called on stage, so that their shyness cannot be seen on their brow, so I, when I go onto the stage of the world where I have only been a spectator until now, step forward with a mask on (larvatus prodeo).” With this confession, the young Descartes seems to have foreseen the scandalous force of his nascent philosophy and so felt the need to wear a mask to protect him.

But the mask, more than the social or hygienic protection it guarantees, more than the image or the character it enhances in the theatre, at parties or in liturgy, has never stopped proclaiming the invincible realm of illusion and appearances. However, this is the policy that has always been assigned to art and even literature. An example: Oscar Wilde and his nephew Arthur Cravan, Marcel Schwob and his niece Claude Cahun, the four of whom were writers, aesthetes, eccentric and profoundly artistic, exalted, without offending their own modesty, the thing that they shared with Descartes and Nietzsche, the multiplicity each one of them had inside. Arthur Cravan embodied this philosophical theatre of the multiple magnificently in his poem “Hie![2]”

“Telluric, chemist, whore, drunk, musician, worker, painter, acrobat, actor;

Old man, child, swindler, scoundrel, angel and reveller; millionaire, bourgeois, cactus, giraffe or deer;

Coward, hero, black, monkey, Don Juan, pimp. lord, peasant, hunter, manufacturer;

Fauna and flora;

I am all things, all men and all animals!”

By playing “Wolf, are you there?”, Carmen Calvo has also delved into the real path of the theatre of multiplicity. A path that was first trodden by the young Dada-Surrealists. As far as Aragon is concerned, let us recall that in his first novel, Anicet ou le Panorama, the protagonist, Anicet, attends a strange ceremony at a mask club, during which seven masked characters, all adorers of the beautiful Mirabelle, the epitome of the modern woman, give him a peculiar or extravagant present. Behind these masks are in fact concealed Jean Cocteau, André Breton, Charlie Chaplin, Marinetti, a Paul Valéry-type savant, Picasso and Max Jacob. Concerning the collagist André Breton, let us recall the final sentence in “L’Année des Chapeaux Rouges[3]” published in Littérature in May 1922, making the Surrealist poet the alter ego of Jacques Vaché in “Le Bal Rouge” or someone like Souvestre and Allain’s Fantômas taken to the screen by Louis Feuillade. “So the walls of Paris had been covered in posters that represented the man in the white mask holding the key to freedom in his left hand: that man was I.” We can add that in 1943 René Magritte, taking at the same time the dust jacket of the first volume of Fantômas and the poster of Feuillade’s film, painted for the first time the typical silhouette of Fantômas in a dress suit and bowler hat dominating the rooftops of Paris in Le Retour de Flamme (The Return of the Flame). It is on the blazing sky that the indolent mask insolently trains the objective, holding a rose in his right hand.

“It was you, Jacques!” wrote and exclaimed André Breton in the collage he sent to Jacques Vaché, thus identifying him with the head of the masked gang. Later evoking the image of a Fantômas in a white mask, André Breton declared from behind the scene, “That man was I”. What about Carmen Calvo? As we have pointed out above, the collagist from Valencia makes a lot of people participate in the game of “Wolf, are you there?” For that reason she does not need to reveal, like her predecessors, her exclusive connections with a gang of criminals, with a club of aesthetes or a circle of conspirers. In her collages, the masquerade of masks is extended to all age groups and all conditions. In a sense, the most spectacular collages where the balaclava helmets, the blindfold, the veil, the ribbon, the make-up or any other disguise or disappearance procedure affect the head or the face, completely or partially, are the ones that have to do with families, groups or assemblies, in such a way that the imposition of a repetitive mask or one with variations ends up revealing the existence of a single family air or collective identity.

The origins of Carmen Calvo’s game of “Wolf, are you there?” are probably Dadaist masks and Surrealist collages. Nevertheless, it has its own rules and runs its own course. The Dadaist-Surrealists wore masks. However, when they felt like it, they took it off. If they had set about conspiring, it was with the intention of showing their faces one day. In this sense, they renovated the art of photomontage in the first issue of La Révolution surréaliste by framing the photograph of the anarchist Germaine Breton with twenty-eight passport photographs and, in the last issue of the magazine, surrounding the painting by Magritte, Je ne vois pas [la femme nue] cachée dans la forêt (I Cannot See [the Naked Woman] Hidden in the Wood), with sixteen photograph-machine pictures of the Surrealists with their eyes closed. Carmen Calvo, for her part, intervenes in a context where the mask occupies a central place. In the first place, let us remember that the young are at the mercy of the adults who make a face for them[4]. Let us say then that the adults, more and more inclined to appreciate immaturity, don the clothes of the young whose faces they have made. Finally let us point out that the individual, in an apparently narcissistic pursuit, is tempted by metamorphoses that do not respect the body or sex or, apparently, the face.

It is from this voluntary and excessive masquerade, which covers all ages and even seems to mock the ravages of time, that Carmen Calvo extracts her collages and manages to outdo the practice of her Surrealist predecessors. The latter, let us not forget, stick back on the pieces of the dismembered body without thinking of attacking the integrity of the face. Three examples of this: 1. the game of the exquisite cadaver is a variation of the reconstruction of the three parts of the body (the head, the trunk and the lower limbs); 2. in the photograph on the cover of the Bulletin international du surréalisme of September 1936, if a mound of roses conceals the face of the woman in Trafalgar Square among the pigeons, it does not in the least spoil her face; 3. René Magritte, who corrects the face several times, adding an apple as a nose in the middle of the face or also, like in his painting Le Viol (The Rape), condensing in the face a woman’s breasts, navel and sex, he reveals the face in concealing it and conceals it in revealing it. The same does not apply to Carmen Calvo’s collage, which by questioning the individual and group portraits of the contemporary masquerade, really comes up against a problem when she discovers how difficult it is to disfigure or recognise someone.

Let us have a look at the collages Virgilio and Oh là là! que d’amours splendides j’ai rêvées! (Oh la la, What Splendid Love Affairs I’ve Dreamt of!). Initially, they are the photographs of two more or less good-looking men. However, the first is submitted to a shower of eyes that land everywhere, including in the character’s sockets, and the second to an avalanche of noodles that stick to his bust, his left profile and his hair, barely respecting his right side, his left eye and the knot of his tie. A more or less heavy shower of eyes also appears in the photograph of a boxer (Sé que he despertado y que todavía duermo [I Know I’ve Awoken and I’m Still Asleep]), and people coming out of a wedding (Testigos [Witnesses]), in the drawing of a young woman hanging by the feet (Son especulaciones casuales e inútiles [They are Useless, Random Speculations]) or that of a girl dancing a few steps (Para darle relieve a mis sueños [To Emphasise My Dreams]). On the subject of pasta, we can also mention the macaroni-type pieces stuck on to the photograph of a smart young man, scattered about his suit and forming rows over all of his head except his eyes and the lower part of his face (El alimento de la sombra [The Food of Shadow]). But what is the meaning of those showers of eyes or pasta or those clouds of shards of glass or pieces of cloth scattered over faces and bodies and sometimes occupying the whole frame? They certainly contribute, like a handful of confetti, to saluting the noise of the parade of masks. In fact, they belong to the numerous diversion or obstruction procedures used by Carmen Calvo in her studies of the face.

When eyes, pasta, shards of glass, etc. appear on the face, the body or the background, we are not far from a viral infection, a disease of the skin or the red spots of an allergic reaction. These rashes, on the other hand, are contagious in Carmen Calvo’s oeuvre. We find their equivalent in several montages of drawings where the faces, bodies or even the clothes are completely covered in daubs, with a fleecy, speckled or stippled appearance. All these skin diseases that are invited to the masked ball seem to want to spoil the fun. On the one hand, Carmen Calvo persists in the art of disguise and does not hide to play “Wolf, are you there?” But, on the other hand, the collagist tempers our ardour by placing incongruent, insignificant or disturbing things on the face, surrounding or blinding the eyes, submitting the face to so much bother that we wonder whether its plasticity, its vitality, its spirituality and its sensibility have simply disappeared.

Everyone knows the famous though of Pascal’s that says, “the greatest spirit of men is not so independent that it is free from being upset by the slightest noise made nearby”. So the squeak of a weathercock or a pulley, or less still, the buzz of a fly, is enough to interrupt the thoughts of the wisest man. What does collagist Carmen Calvo do? Even when she preserves the anonymity of the face by unfurling all the devices of masks, she also dedicates herself, with the aid of string, twine and little objects hanging on the face, to let us hear the buzz of an external agent, of an insignificant intruder that does not fail to disturb us.

Carmen Calvo the collector

Carmen Calvo dedicates herself to the photographic collage but also to several tasks of recuperation and confrontation of objects. On a large-format piece of cork, she hangs, sews or nails a whole range of objects or bits of objects. Any one of these intruders, if it had been inserted in the magnetic field of the face, would not have failed to alter it. But the collector, who makes an abstraction of the face here, has decided to gather these unusual fragmentary objects in order to calibrate them by measuring them with others, sometimes at the risk of isolating just one against the same black cork background. These assemblages could be said to be the other side, but the positive side, of the photographic collages of masked faces. Because as the face is weakened, it fades and dissolves in the “Wolf, are you there?” collages, the little pile of objects confronting each other in these assemblages acquires new health. An orthopaedic insole, a graduated ruler, a horseshoe, a suitcase, a clock quadrant, a spatula, a paintbrush, a funnel, a clothes-hanger, a high-heeled shoe, a piece of string, a blackboard, a bandage, a shoetree, an enamel number, a flower, a belt, a pharmaceutical phial, a fragment of a celluloid baby, a pink cross, a mannequin’s bust covered with multicoloured pins, a framed photograph, an eye, etc., all these articles of different origins –extracted among other things from passementerie vendors, watchmakers’ or leatherwork shops– all this waste material, which does not disdain the new or the patina of time, shines unashamedly for having been selected for this list of honour. Carmen Calvo does not use magic or affection. It does not matter whether the list of objects is long or short, her assemblage art remains simple and discreet.

Alongside assemblages on black cork are numerous assemblages on a golden background that demonstrate that Carmen Calvo feels tempted by a much more formal pursuit. Then the elements no longer seem destined to be invented and identified as such, but to be linked to each other as though they form an entity in their own right or an original figure thanks to their conjunction. On the other hand, in these constructive-type assemblages it is often difficult to tell the nature or origin of the elements used. It also happens that the collector Carmen Calvo ventures into the terrain of repetition, lining up dolls’ legs or signs of pseudo-writing. We must not forget that she was soon to address the issue of series with Paisaje, Serie recopilación y reconstrucción (Landscape, Compilation and Reconstruction), and later Series Escrituras (Writing Series).

What does an assemblage contribute that a collage does not? We have seen that in the “Wolf, are you there?”·game, initially intended to preserve the anonymity of the mask-wearer, actually pointed out a defect in personal identity, a mortal blow to the plasticity of the face. Which makes us understand, among other things, that Carmen Calvo’s photographic portraits are not in the least narcissistic. On the contrary, the fact that in 1994 she entitled an assemblage of some hundred objects Autorretrato (Selfportrait) proves that the Spanish artist endows the object, or rather the multiplicity of objects, with a certificate of subjectivity. Furthermore, for a collage of photographs portraying numerous objects in situ, Carmen Calvo does not hesitate to use the same interrogative formula with an affirmative meaning on two occasions, in 1997 and 1998: ¿Qué hay en todo esto sino yo? (What is There in All this but Me?). For her, the matter is clear, the objects and even the fragments of objects possess the parcel of subjectivity usually reserved for the personal expression of a word or a face.

One of the characteristics of Carmen Calvo’s assemblages and her collages resides in her recurrent way of presenting the object, by hanging it from a thread, a rope, a piece of ribbon or twine. Let us concentrate on the function of all these strings, setting aside their function of attaching the object to the support and their function of concealing the eyes or the face. Let us mention some remarkable cases like Los ojos de los pobres (The Eyes of the Poor), Alegría es uno de sus adornos más vulgares (Gaiety is one of Her More Common Ornaments), Habla de exóticas cosechas (It Speaks of Exotic Crops). He aquí como ocurrió (This is How it Happened), El gran teatro del mundo (The Great Theatre of the World), Le Châtiment de Tartuffe (Tartuffe’s Punishment), Todos los rostros del pasado (All the Faces of the Past) and, very specially, Délires (Deliriums), in which, in this case, the hanging object is a sparrow whose beak and eyes are tied by a blue ribbon and which is partly wrapped up. It is to be expected that the sight of a sparrow hanging from a piece of twine and wrapped up in a ribbon will elicit delirious questions and answers. This is, on the other hand, the subject of Cosmos, Witold Gombrowicz’s latest novel, at the beginning of which there is, on the one hand, a sparrow hanging by a piece of wire from a branch and, on the other, the association the narrator establishes between Catherette’s deformed mouth and Léna’s virginal lips. At the end of this “detective novel”, the narrator discovers Lucien, Léna’s husband, hanging from a tree; he puts his hand up to the corpse and sticks a finger in his mouth.

For Gombrowicz in Cosmos, it is not possible to put your feet in nature or remain in its habitat without being assaulted by different signs, all equally insignificant, but which seem to us like indications or arrows leading somewhere. To sum up, it is a kind of general theory about the delirium of interpretation, of which Dalí’s paranoid-critical theory would be the restricted one. In fact, Carmen Calvo’s collections of objects, sometimes reduced to a single element, make us enter that Gombrowiczian cosmos of tangible signs that challenge reason so that it will connect them and sketch their prolongation. Then we have to say whether the object is a thing and a sign for Carmen Calvo. Let us remember that the nature of a thing is to be identical to itself and not to refer to anything but itself, whereas the essence of a sign is to be a thing that refers to something else. Carmen Calvo is too much of a naturalist not to conceive her found objects as things, but she is too imaginative not to see them as signs related to an emotion, a passion or a story.

That is why Carmen Calvo’s collections of objects vie for a place in the glass cases of an archaeological or a natural history museum and, on the other hand, in a list of clues drawn up by a person investigating a crime or a lover in a passionate love affair. On the other hand, the enigmatic titles of the works, sometimes taken from Arthur Rimbaud or Marcel Duchamp, seem to want to show that the objects exhibited correspond to the principal pieces in the dossier of an extremely important affair and that examining the objects in question would permit us to discover the key to the whole matter. In essence, the objects or fragments of objects collected by Carmen Calvo are: 1. tangible material objects, in other words, things; 2. records and other ribbons that mark the pages of the book of life; 3. clues to an enigmatic affair that is to be resolved or images from the private or public sphere; 4. the pieces of a vast collection of objects that the artist has gathered in all her oeuvre. But, let us remember, as a collagist, the Valencian artist stages the disappearance of the face and, as a collector, she underscores the force of attraction of an object or a series of objects.

Does Carmen Calvo the object collector give in to a fetishistic compulsion? Has she perchance been in contact with sado-masochism that she resorts so often to restraints, straps, hanging or masks? Is she so obsessed or tormented by childhood that she disarticulates many dolls and makes many drawings of children? In other words, does Carmen Calvo resort to psychology and run after her autobiography?

Carmen Calvo, the interior architect

However much Carmen Calvo plays “Wolf, are you there?” and collects objects as if they were fetishes or toys, she is not satisfied to reinterpret her biography as a child or an adult. She would rather keep her distance from her childhood. She would even call herself a pedagogue, a little like Jean Jacques Rousseau in Émile ou de l’éducation. As regards the education commended by Rousseau, make no mistake, it is not natural or spontaneous, but artificial and calculated. Indeed, Émile’s preceptor achieves his aims by using all sorts of stratagems and settings. Whereas Carmen Calvo plays and makes us play “Wolf, are you there?”, Émile’s teacher praises in the matter an absolutely theatrical lesson, “All children are afraid of masks. I’ll start by showing Émile a mask of a pleasant face; then someone will put the mask on; I’ll start laughing, everyone will laugh and the child will laugh like everyone else. Little by little I will get him used to less pleasant masks and finally horrible faces. If I’ve handled the degrees properly, instead of being frightened by the last mask, he’ll laugh as he did at the first one. After that I won’t be afraid he’ll be frightened of masks.” This passage from the first book of Émile ou de l’éducation is interesting for two reasons, for Jean-Jacques Rousseau and for Carmen Calvo. As far as Rousseau is concerned, it is interesting to wonder whether the first statement, “All children are afraid of masks” should not be replaced by this other one, “Some children are afraid of some human faces”, which has a totally different anthropological and moral scope; for the problem is not to protect oneself from masks, which, on the other hand, are not too commonly seen in the street, but of preserving oneself from some physically or morally horrible faces of the human race; the masquerade imagined by Rousseau is a pedagogic rite of initiation in society. As regards Carmen Calvo, in whom all adults, all children and even some animals wear masks, the ceremony or the game of “Wolf, are you there?” has the function of conjuring not the horrible face of one individual or another but a real failing or lack to be found in all human faces.

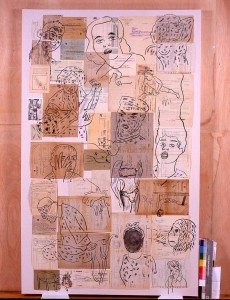

In numerous drawings and collages on a background of writing, the artist from Valencia generously mixes all ages. She does not do so specifically to repeat, after Freud, that the child is perverse and polymorphous. Let us see in this sense the collage Tus labios son tórtolas mudas (Your Lips are Dumb Turtle Doves), of 2001. Upholstered with capital or typed letters, notes from hotels, colour illustrations, a telegram but also with a fan bearing flowers and a bird, this drawing is covered with drawings that look like sketches or rather a sort of skilfully dislocated exquisite corpses. Let us name the subjects of the drawings: a blue lunar face, a frog next to two birds, the bust of a child whose arm is prolonged into a foot, the head of a man in profile, a little girl’s head in a blue turban, a red-painted face in profile, a woman in a red beret whose nose has a large appendix attached to it, a little boy with his hand on his cap, two garments of clothing next to each other, a baby’s face, a child’s hand underneath an oblong balaclava helmet for a Cyclops or a one-eyed person, a wolf’s mouth and two paws, the outline of a corpulent, headless Arab woman, the face of a boy with his mouth open, the face of an Arab woman covered from head to foot whose head seems to be crowned by a taro, a character hidden by the sweater he or she is taking off, a woman with a blindfold, a girl in a swimsuit wearing a red mask, the bottom of a body paddling in the water, the profile of a female head. If we add to these drawn motifs four colour images, we cannot fail to be surprised at the number of hats and masks and the presence of children. The drawing of the mask convinces us once again that children and adults are all playing hide-and-seek, but without being able to say that some are in the “green paradise of childhood loves” and the others hide behind the “black ocean of the filthy city”[5]. Carmen Calvo discovers that modernity has invented, after the heterogeneity of sexes, the heterogeneity of ages, a heterogeneity favoured by the exchange or circulation of masks.

“Y QUE CANTE UNA NANA CUAL NIÑOS MORIBUNDOS” 2005

In the same way as Bellmer’s La Poupée cannot be reduced to sexual perversion, Una jaula para vivir (A Cage to Live in), that place for putting dolls, toys and mannequins of children conceived by Carmen Calvo, or Una Mirada escenográfica (A Theatrical Gaze), the spectacular series of boxes dedicated to the same age group, cannot be assimilated in a children’s theatre. For that theatre is for other age groups too. When a child wears a mask, a bandage, a balaclava helmet, or even a muzzle, it reminds us that children often dress up and sometimes a child is kidnapped, but it also makes one think that a human being, of whatever age, can and, why not, should wear a muzzle.

Let us go back for a moment to Carmen Calvo’s drawings and collages on a background of writing, which undoubtedly have to do, as far as writing and collage are concerned, with André Breton’s collage-letters of 1918-19. However, as far as the drawing is concerned, we would have to mention Yves Tanguy’s intervention when he fills in by hand in ink on the pages of the dictionary the vignettes of famous men: Henry II transformed into a mermaid, Titus with his dog Ticianus on a lead, Alexander Magnus going off on campaign with a rucksack on his back and a pipe in his mouth, Eugène Labiche as a legless cripple or Alfred de Vigny sitting with his legs stretched out in front of him and shedding large tears[6]. Like Breton, Calvo has mixed writing and image. Like Tanguy, she has prolonged busts and faces, without resorting to caricatures.

Nevertheless, Carmen Calvo has adopted a principle that she tends to use in all her collages, her assemblages or her installations and that distinguishes her from her Surrealist predecessors. This principle could be called an “architectonic principle”, for it is inspired by four architectonic categories: façade, scale, matter and vacuum. Whether decorated or plain, the façade presents bays or is blind; it is like the skin or the shop window of a building. The scale of a building adjusts to the functions of the work and depends on the context. The matter always imposes its conditions on the construction project. Finally, the vacuum is what has to be sculpted or contained –in the two meanings of the verb contain.

Let us now examine the assemblages on black cork or gold. We can consider the objects tied to or hanging from these vertical supports as the bays or decorations of a façade, sometimes with a few openings, others with decorative friezes due to the ordered abundance of objects arranged and fixed to the façade.

On the contrary, it is the matter of the collage that is underscored in photographic collages. Either the paint is applied or placed as though on a glass, or a piece of string, a ribbon, an object, hanging or stuck, stands out in the foreground. This matter, often coloured, emphasised, indicates that it is a collage, but an architectonic collage, with colour or the object applied to the façade and the body of the building in the background, in this case reduced to a photographic portrait.

As regards the collages of hand-written, typed or printed documents, covered in drawings, we might think at first sight that the documents are a background or support for the drawings. A structural or architectonic point of view heads us in another direction. These documents would be windows or openings in a façade that would give on to portraits or scenes of private lives. Besides, in this architectonic context, there would be ruptures or changes of scale, by means of colour images or pages from fashion magazines that would indicate not interior but exterior scenes.

That Carmen Calvo comes across as an architect and above all as an interior designer is still more manifest in her installations, sculptures or boxes. The vacuum and the matter are called upon here. The objects in the assemblages are retrieved here, the obsessive faces of the drawings are materialised, the photographs recycled.

In 1982, the sculptor and landscape artist Isamu Noguchi subverted matter when he made Magritte’s Stone, a sculpture in galvanised steel dipped in molten zinc that gave the surface the pointillist white and grey speckled appearance we can find in the pebbles in river beds or the rocks of torrents. And as the sheet of fine galvanised steel had the shape of a rock or an enormous pebble, no mistake could be made, this steel object on a steel stand had all the appearance of a stone sculpture although it was really only a thin sheet of galvanised steel.

In her works of interior architecture, Carmen Calvo has also played with surfaces and volumes, matter and form, words and images. She has succeeded in realising that the conjunction of matter and vacuum endowed the object with a complete form. She has caressed the faces in her photographic collages and imitated the parts of the body in her drawings. In adopting large formats, she has tackled the sculptural or architectonic dimension. She has set about conquering imagery, going straight from the baby’s dribbler to the dog’s muzzle.

She has kept her feet on the ground by boldly mixing different planes, playing with concealing and overlapping, revealing the mirror and breaking the glass.

She is an artist who draws us into her dreams or who makes us touch an unnoticed reality with our finger. Carmen Calvo is doubly an artist. With her childhood dreams she invites us to play “Wolf, are you there?” With her adult intuitions, she brings to light a large number of objects from everyday life, from a spatula to a bandage or a doll. The latter precisely, presented with all her seams, bald or with hair, naked or dressed, in equilibrium or upside down, above all, is not a ghost. In fact, dolls and mannequins have become puppets for the old and the young. Collectively or individually, it is hard for us to look in the mirror. We are not very sure who or what we look like. No doubt that is why we bend over unsteady puppets with blurred features. Puppets that look rather like the strange manikins painted by Giorgio de Chirico in 1915, those enigmatic creatures with cut-off arms and smooth faces in paintings like Le Vaticinateur (The Seer), Le Poète et le Philosophe (The Poet and the Philosopher), Le Duo (The Duo, also known as Les Mannequins à la tour rose), the fragmented characters showing the hollow inside of the bust or the head in Les Contrariétés du penseur, La Lumière fatale, or in the drawings La Mélancolie and Mannequin avec perspective [Melancoly, Mannequin in Perspective].

Who has robbed us of the image? Or rather, how can we escape from the countless images sent to us by television screens, surveillance cameras, digital photograph machines? “Mind the paint,” they said. Mind the photography now. Carmen Calvo drags us into her camera obscura to dream of the wolf in colour.

Georges Sebbag

Notes

[1] See Georges Sebbag, L’Imprononçable jour de sa mort, Jacques Vaché janvier 1919, with the facsimile of André Breton’s collage-letter. Jean-Michel Place, Paris 1989.

[2] Arthur Cravan published his poem “Hie!” in July 1913 in the second issue of the magazine Maintenant, in which he was the only writer.

[3] “L’Année des Chapeaux Rouges” by André Breton appeared in Littérature, new series, no. 3, 1st May 1922. this text was reproduced at the end of Poisson soluble, which, let us remember, came after the Manifeste du Surréalisme in October 1924, as an explanation or a poetic illustration of the concept of Surrealism.

[4] In Ferdydurke (1937), the Polish novelist Witold Gombrowicz shows how the adults, aka the Mature, manufacture the faces of the young, aka the Green, and infantilise them.

[5] Charles Baudelaire, “Moesta et errabunda”, Les Fleurs du mal.

[6] Yves Tanguy, “En marge des mots croisés”, Documents 34. “Intervention surréaliste”. Brussels 1934.

Références

Georges Sebbag, “Wolf, Are You There?”, published in catalogue Carmen Calvo, Ivam, Valencia, 2007.