Indifferent people are not exuberant. They are minimalists of sensibility and reason. Emotionally, they are characterized by feeling an absence of feeling. Rationally, they see the principle of reason as being insufficient. Which is why reality is not very real for them. Because they doubt their own subjectivity, indifferent people make the real less real, moving it onto the plane or the plateau of what is imaginary.

The call of the void

Indifferent people see the formless as much as the form, the void as much as the solid. As Lao-Tseu said: “Doors and windows are put in to make a house. Their emptiness governs its use”.

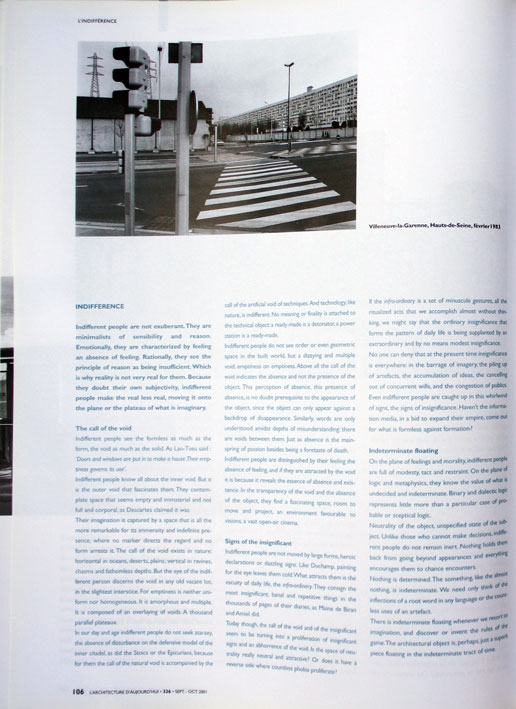

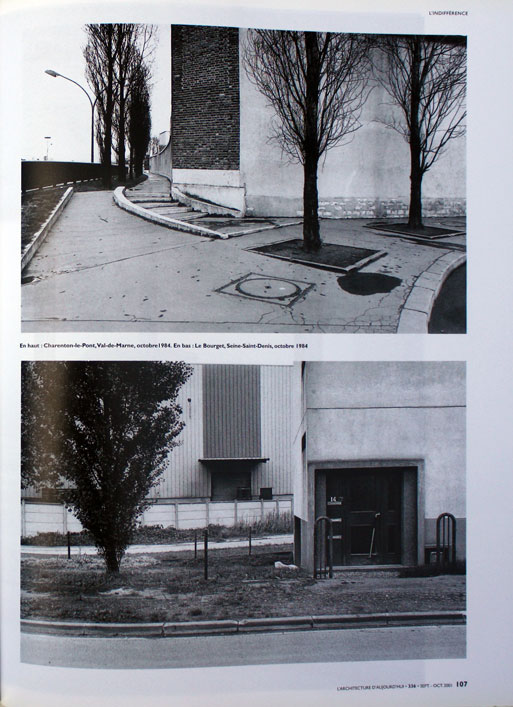

Indifferent people know all about the inner void. But it is the outer void that fascinates them. They contemplate space that seems empty and immaterial and not full and corporal, as Descartes claimed it was.

Their imagination is captured by a space that is all the more remarkable for its immensity and indefinite presence, where no marker directs the regard and no form arrests it. The call of the void exists in nature: horizontal in oceans, deserts, plains; vertical in ravines, chasms and fathomless depths. But the eye of the indifferent person discerns the void in any old vacant lot, in the slightest interstice. For emptiness is neither uniform nor homogeneous. It is amorphous and multiple. It is composed of an overlaying of voids. A thousand parallel plateaux.

In our day and age indifferent people do not seek ataraxy, the absence of disturbance on the defensive model of the inner citadel, as did the Stoics or the Epicurians, because for them the call of the natural void is accompanied by the call of the artificial void of techniques. And technology, like nature, is indifferent. No meaning or finality is attached to the technical object: a ready-made is a detonator; a power station is a ready-made.

Indifferent people do not see order or even geometric space in the built world, but a dizzying and multiple void, emptiness on emptiness. Above all the call of the void indicates the absence and not the presence of the object. This perception of absence, this presence of absence, is no doubt prerequisite to the appearance of the object, since the object can only appear against a backdrop of disappearance. Similarly, words are only understood amidst depths of misunderstanding: there are voids between them. Just as absence is the mainspring of passion besides being a foretaste of death.

Indifferent people are distinguished by their feeling the absence of feeling, and if they are attracted by the void it is because it reveals the essence of absence and existence. In the transparency of the void and the absence of the object, they find a fascinating space, room to move and project, an environment favourable to visions, a vast open-air cinema.

Signs of the insignificant

Indifferent people are not moved by large forms, heroic declarations or dazzling signs. Like Duchamp, painting for the eye leaves them cold. What attracts them is the vacuity of daily life, the infra-ordinary. They consign the most insignificant, banal and repetitive things in the thousands of pages of their diaries, as Maine de Biran and Amiel did.

Today though, the call of the void and of the insignificant seem to be turning into a proliferation of insignificant signs and an abhorrence of the void. Is the space of neutrality really neutral and attractive? Or docs it have a reverse side where countless phobia proliferate?

If the infra-ordinary is a set of minuscule gestures, all the ritualized acts that we accomplish almost without thinking, we might say that the ordinary insignificance that forms the pattern of daily life is being supplanted by an extraordinary and by no means modest insignificance.

No one can deny that at the present time insignificance is everywhere: in the barrage of imagery, the piling up of artefacts, the accumulation of ideas, the cancelling out of concurrent wills, and the congestion of publics. Even indifferent people are caught up in this whirlwind of signs, the signs of insignificance. Haven’t the information media, in a bid to expand their empire, come out for what is formless against formation?

Indeterminate floating

On the plane of feelings and morality, indifferent people are full of modesty, tact and restraint. On the plane of logic and metaphysics, they know the value of what is undecided and indeterminate. Binary and dialectic logic represents little more than a particular case of probable or sceptical logic.

Neutrality of the object, unspecified state of the subject. Unlike those who cannot make decisions, indifferent people do not remain inert. Nothing holds them back from going beyond appearances and everything encourages them co chance encounters.

Nothing is determined. The something, like the almost nothing, is indeterminate. We need only think of the inflections of a root word in any language or the countless uses of an artefact.

There is indeterminate floating whenever we resort to imagination, and discover or invent the rules of the game. The architectural object is, perhaps, just a superb piece floating in the indeterminate tract of time.

Georges Sebbag

Références

Georges Sebbag, « Indifference », L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui, n° 336, septembre-octobre 2001. Version anglaise du texte en français « L’indifférence » publié dans la revue.

« Indifference » en anglais est repris dans Basa, n° 25, second semestre 2001 [parution effective, juillet 2002], Santa Cruz de Tenerife, publicacion del colegio de arquitectos de Canarias. Basa n° 25publie aussi la traduction de « L’indifférence ». en espagnol (« El indiferente »).

Rappelons que L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui n° 336 publie deux textes de Georges Sebbag sur l’indifférence (en français et en anglais) : « Indifférent comme un ready-made » et « L’indifférence ». Peu après, Basa n° 25 publie trois textes de Georges Sebbag sur l’indifférence (en espagnol et en anglais) : « L’indifférence », « Indifférent comme un ready-made » et « Images taoïstes ».